The movement of people was integral to the inception of the

Kingdom of Kongo and its systems of labor. In the early 15th century Kingdom of

Kongo founder Lukeni lue Nimi moved the capital of the loose federation of

communities under his control to a mountainous area originally ruled by

Mabambolo Mabpangalla. It is here where we gain the first reference of slavery

in Kongo. Mambabolo Manpagalla was defeated and his descendants were said to

have been either driven out or taken as slaves. While a great deal of

information is not known about the Kingdom of Kongo's use of slaves before

Portuguese arrival, it is fairly accepted that most of the slaves used by the

Kingdom were foreign captives, taken in through Kongo's military expansions and

civil wars. The majority of people born in Kongo were protected from becoming

slaves and facing exportation. This would change as the Portuguese would become

more insatiable with their need for labor, and internal political conflicts

would lead to the fragmentation of the kingdom's centralization allowing some

native born Kongo to be taken as slaves.

A Kingdom of Town and

Country

Historian John K Thornton, describes Kongo as being made of two

economic sectors- the royal city of Sao Salvador and the countryside- both

sectors dominated by the state. The countryside relied on a village style

economy, which was common in much of central Africa. In this style economy,

land was communally owned, maintained, and harvested between households that

controlled the production and dissemination of goods. While life revolved

around labor for nearly all members of Kongo society, exempting the very elite,

there was a division of labor between men and women. Men would typically take

on the role of clearing forests, producing palm wine and oil, hunting, and

participating in the long distance trade of food goods, slats, animal hide,

metals, and fabrics. Women would do varied agricultural cultivation, care for

domestic animals, and run household work. This form of village economy would

produce a social surplus, which would be subjected to a small consuming class

of village rulers and also used to support the taxes required by the state. To

maintain centralization and their upperclass lifestyle, large sections of the

urban elite were sent to live in the countryside for periods of time to

regulate the collection of taxes. Kongo villages were mainly self-sufficient,

but there was a fairly large local market and trade system, which suggests the

presence of specialized labor.

Historian John K Thornton, describes Kongo as being made of two

economic sectors- the royal city of Sao Salvador and the countryside- both

sectors dominated by the state. The countryside relied on a village style

economy, which was common in much of central Africa. In this style economy,

land was communally owned, maintained, and harvested between households that

controlled the production and dissemination of goods. While life revolved

around labor for nearly all members of Kongo society, exempting the very elite,

there was a division of labor between men and women. Men would typically take

on the role of clearing forests, producing palm wine and oil, hunting, and

participating in the long distance trade of food goods, slats, animal hide,

metals, and fabrics. Women would do varied agricultural cultivation, care for

domestic animals, and run household work. This form of village economy would

produce a social surplus, which would be subjected to a small consuming class

of village rulers and also used to support the taxes required by the state. To

maintain centralization and their upperclass lifestyle, large sections of the

urban elite were sent to live in the countryside for periods of time to

regulate the collection of taxes. Kongo villages were mainly self-sufficient,

but there was a fairly large local market and trade system, which suggests the

presence of specialized labor.

The city of Sao Salvador was surrounded by large agricultural

plantations that were worked by slaves. These plantations would support the

city's need for food, as bulk transportation of goods from the outer towns and

villages was time consuming and difficult. Evidence suggests that the slaves

working on these plantations faced a fair amount of autonomy. While they worked

on producing foods for the nobility, they were allowed to run their own

self-sufficient households and were integrated into the villages. Therefore,

the slave masters did not hold complete control over their lives as they did in

other plantation labor systems across the Atlantic. While there was a fair

amount of economic leeway across the Kingdom of Kongo, both the villages and

towns were dominated politically and economically by the representatives of

Kongo's ruling class.

The Portuguese, Internal

Politics, and Slavery

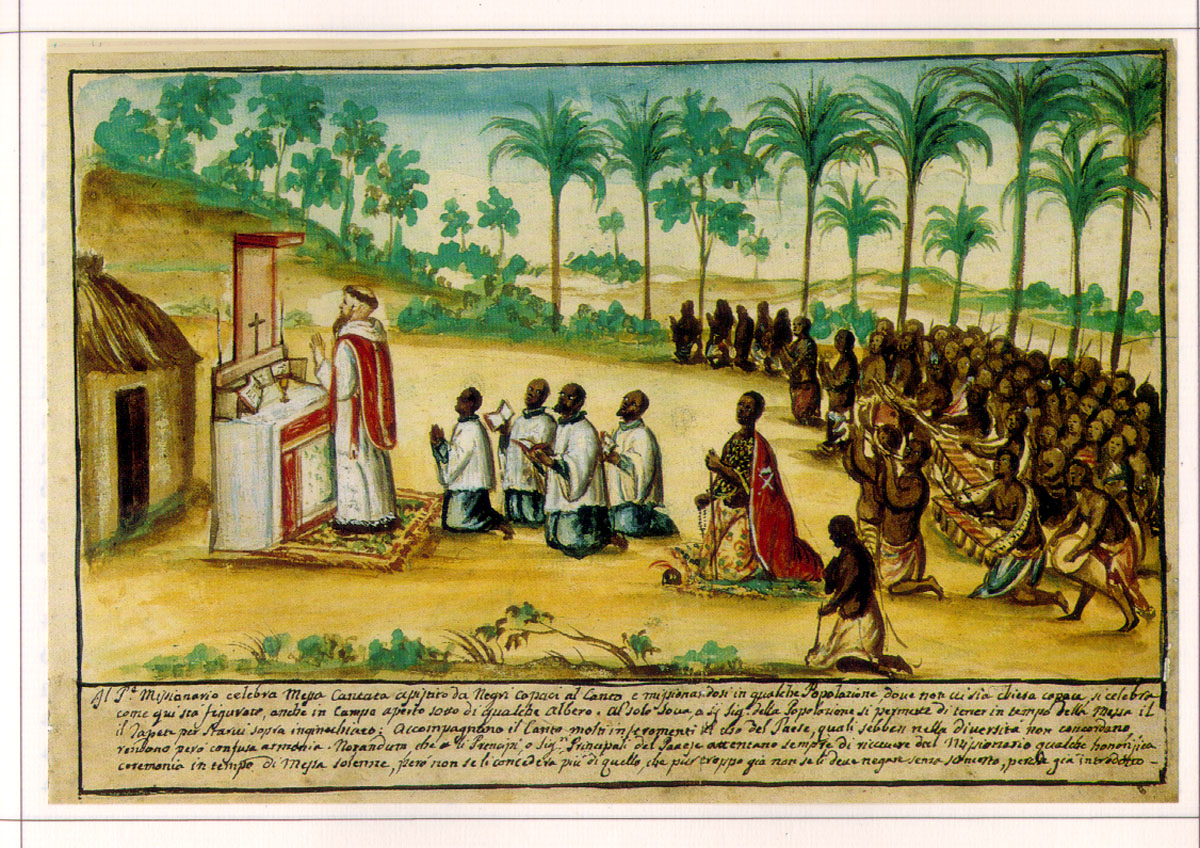

The movement of the Portuguese into Kongo in the late 15th century

brought change to the region's politics, religion, and regulation of labor,

although there is debate over how much of that change was due to the Portuguese

or to internal Kongo politics. Allowing that the Portuguese did have some

amount of influence on the Kongo people and political system, and that this

relationship was not one-sided for the rulers of Kongo, we can view changes in

the Kingdom of Kongo as a mixture of external and internal actions and

reactions. Very early on in the Portuguese-Kongo relationship there is an

example of the effects of the shifting of people. In the 1470s, Portuguese

sailors had claimed the island of Sao Tomé off the western coast of Africa. In

Sao Tomé they created large sugar fields, which required large amounts of

labor. After establishing relations with Kongo, the Portuguese looked to the

kingdom to provide labor for Sao Tomé and other Portuguese territories. King

Afonso, traded slaves as commodity exports to the Portuguese, but took issue

with Portuguese traders going outside of the established system and capturing

those who were not deemed as slaves in Kongo. He writes to Portugal about the

effect of the displacement of people on the Kongo population and the Portuguese

circumventing of the trade system's effect on the internal political structure of

Kongo society. For example, Portuguese traders began forgoing the long journey

to the capital to retrieve slaves and began trading in the coastal town of

Soyo. Officials in this province, which was intentionally kept relatively

impoverished in order to suppress political power, became wealthy from this

trade and an alternative localized economy was developed weakening the central

authority. In next week's post I will expand upon the conflicts that followed

the movement of people through the lens of the TransAtlantic Slave Trade.

Birmingham, David. 1965. “SPECULATIONS ON THE

KINGDOM OF KONGO”. Transactions of the

Historical Society of Ghana 8. Historical Society of Ghana:

1–10.

Heywood, Linda M.. 2009. “Slavery and Its

Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800”. The Journal of African History 50

(1). Cambridge University Press: 1–22.

Thornton, John. 1977. “Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550-1750”. The Journal of African History 18 (4). Cambridge University Press: 507–30. http://www.jstor.org.libdata.lib.ua.edu/stable/180830.

Thornton, John K.. 1982. “The Kingdom of Kongo,

Ca. 1390-1678. The Development of an African Social Formation (le Royaume Du

Kongo, Ca. 1390-1678. Développement D'une Formation Sociale Africaine)”. Cahiers D'études Africaines 22

(87/88). EHESS: 325–42. http://www.jstor.org.libdata.lib.ua.edu/stable/4391812.